Like a lot of people, I came to the area of physiological computing via affective computing. The early work I read placed enormous emphasis on how systems may distinguish different categories of emotion, e.g. frustration vs. happiness. This is important for some applications, but most of all I was interested in user states that related to task performance, specifically those states that might precede and predict a breakdown of performance. The latter can take several forms, the quality of performance can collapse because the task is too complex to figure out or you’re too tired or too drunk etc. What really interested me was how performance collapsed when people simply gave up or ‘exhibited insufficient motivation’ as the psychological textbooks would say.

People can give up for all kinds of reasons – they may be insufficiently challenged (i.e. bored), they may be frustrated because the task is too hard, they may simply have something better to do. The prediction of motivation or task engagement seems very important to me for biocybernetic adaptation applications, such as games and educational software. Several psychology research groups have looked at this issue by studying psychophysiological changes accompanying changes in motivation and responses to increased task demand. A group led by Alan Gevins performed a number of studies where they incrementally ramped up task demand; they found that theta activity in the EEG increased in line with task demands. They noted this increase was specific to the frontal-central area of the brain.

We partially replicated one of Gevins’ studies last year and found support for changes in frontal theta. We tried to make the task very difficult so people would give up but were not completely successful (when you pay people to come to your lab, they tend to try really hard). So we did a second study, this time making the ‘impossible’ version of the task really impossible. The idea was to expose people to low, high and extremely high levels of memory load. In order to make the task impossible, we also demanded participants hit a minimum level of performance, which was modest for the low demand condition and insanely high for the extremely high demand task. We also had our participants do each task on two occasions; once with the chance to win cash incentives and once without.

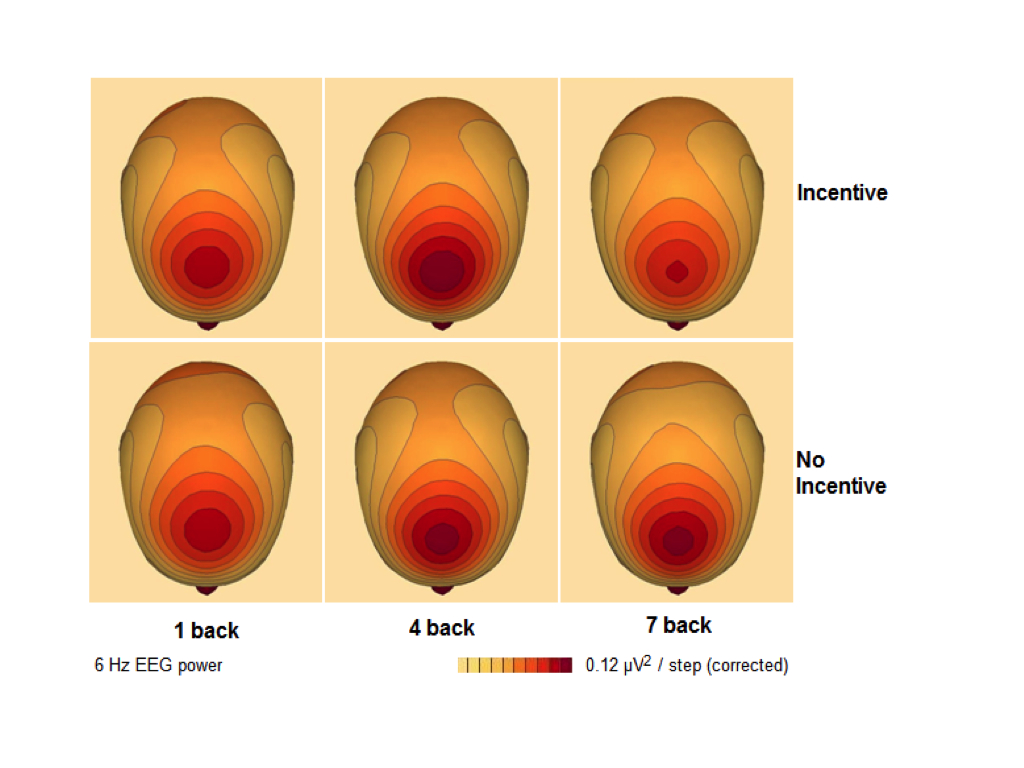

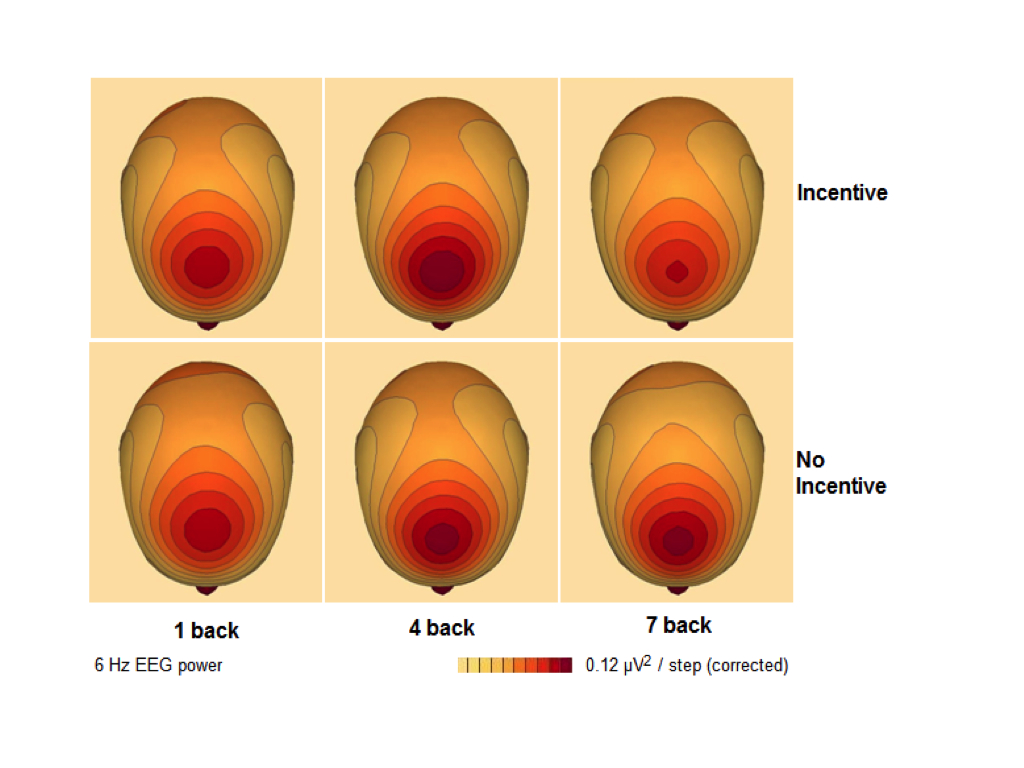

The results for the frontal theta are shown in the graphic below. You can clearly see the frontal-central location of the activity (nb: the more red the area, the more theta activity was present). What’s particularly interesting and especially clear in the incentive condition (top row of graphic) is that our participants reduced theta activity when they thought they didn’t have a chance. As one might suspect, task engagement includes a strong component of volition and brain activity should reflect the decision to give up and disengage from the task. We’ll be following up this work to investigate how we might use the ebb and flow of frontal theta to capture and integrate task engagement into a real-time system.